Syntax Is Cheap. Paradigms Matter.

2025-11-09

What if the programming industry’s decades-long obsession with unified languages is solving the wrong problem entirely?

We’ve spent fifty years trying to build the One Language To Rule Them All. Each generation promises that this time we’ll finally unify every useful paradigm—functional, imperative, concurrent, logic—into a single coherent whole. Yet here we stand in 2025, still arguing about whether Rust’s borrow checker or TypeScript’s unsound gradual typing finally cracked the code.

They didn’t. Because they couldn’t. We’ve been chasing a mirage.

The 1970s Trap

In 1972, CPUs were expensive. Memory was expensive. Programmer time, relatively speaking, was cheap. You couldn’t afford multiple compilers, multiple runtime systems, multiple tool chains. So you picked one language and made it stretch across every problem domain you encountered.

This wasn’t wrong. This was rational.

Fast forward to 2025. CPUs are practically free. Memory costs nothing. A decent laptop has more computing power than entire data centers had in 1972. Yet we’re still building languages like we’re rationing silicon.

Look at the contemporary language wars. See those endless debates about whether to add async/await to language X, or whether language Y should support both OOP and functional patterns? That’s us still trying to solve the 1972 problem. We changed the world. Then pointed at our old tools and said they’re still the right abstraction.

The Breakthrough: Mature Lisp as LCD

Here’s what the last decade of tooling has quietly revealed: syntax is cheap, paradigms are expensive.

Mature, production-quality implementations of Common Lisp give us something remarkable. They’re kitchen sinks—supporting every paradigm you might need—but with deliberately limited syntax. That syntax is commonly dismissed as “unreadable,” yet it turns out to be profoundly machine-readable and machine-writable. Like assembler, but without the line-oriented restriction.

This isn’t a bug. It’s an overlooked feature.

By wrapping custom syntaxes over Common Lisp, programmers can whittle deep thought down to the bone. Each paradigm gets syntax tuned for its specific needs, while still producing code that actually runs. This is how all programming languages work—they produce running machine code.

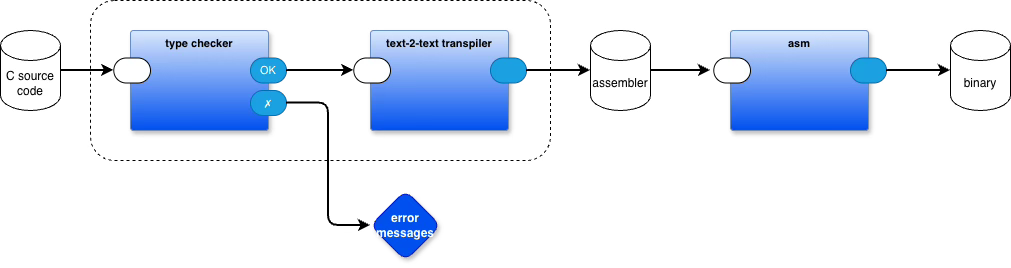

The relationship was just more apparent in the early days, when C compilers emitted assembler text, and assembler programs converted that text into bags of bits that could be loaded and run.

The paradigm expressed in the code matters deeply.

The concrete syntax used to express it? That’s just typographical preference.

Common Lisp is an LCD (lowest common denominator) for semantics, not because its syntax is pleasant for every problem, but because S-expressions provide a universal intermediate representation that’s trivial for tools to manipulate.

Current tools like OhmJS and text-to-text transpilers make this concrete. You can transform between syntaxes mechanically, reliably, quickly. I came to this realization gradually, working with S/SL years ago, watching how straightforward syntax transformation could be. But seeing how early C compilers worked—as simple text-to-text transmogrifiers, C to assembler, no grand unified IR required—crystallized it completely.

Peepholing: The Lost Technique

Let me tell you about a compiler optimization technique that’s been hiding in plain sight for forty years.

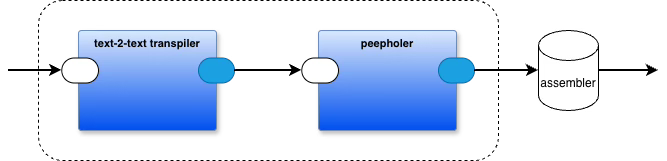

Peepholing works like this: you run a small window—two, three lines—down your emitted code, matching patterns and replacing them with better equivalents. Originally this meant assembler. You’d look for sequences like “load register, add one, store register” and replace them with “increment register.” Simple. Brutally effective.

Fraser and Davidson formalized this in their 1980 paper on retargetable peephole optimizers. They invented RTL—Register Transfer Language—as an intermediate representation close to assembly but abstract enough to be machine-independent. The technique became foundational. GCC still uses it.

But here’s what almost everyone missed: peepholing isn’t about assembly language. It’s about pattern-matching sequential operations and replacing them with better equivalents.

Fraser and Davidson worked at the register-transfer level because that’s where they could see the patterns in 1980. Their tools could only pattern-match flat, line-oriented text. So they targeted assembler.

We don’t have that limitation anymore.

PEG Changes Everything

OhmJS and other PEG-based tools let you pattern-match structured, nested text. The kind of text that modern high-level languages produce. Rust. Clojure. C++. Lisp. Python. JavaScript.

This means you can apply the peephole strategy to actual programs, not just their assembly output. You can match lumps of high-level code and replace them with better lumps of high-level code. The technique scales up from registers to functions, from machine instructions to paradigms.

Jim Cordy understood this. His OCG (Orthogonal Code Generation) work invented a middle language—higher level than assembler, lower level than most high-level languages. Instead of variables, it uses data descriptors. This normalized combination produces an internal form that is highly machine-writable and machine-readable, compared to the mish-mosh of “readable” languages that target human-readability instead of greasing the skids for machines.

This normalization lets you write programs that write programs—a higher form of compilation. You can write programs that insert information into code, like hanging baubles on a Christmas tree. You can write programs that wring assembler and machine code out of normalized intermediate representations. You can write decision trees that customize generated code based on the abilities of specific targets—what used to mean compiling for different CPU architectures, but now can mean transmogrifying code for specific underlying high-level assemblers like JavaScript, Python, or Common Lisp.

My PML Experience

Let me make this concrete. I needed to write a kernel for my PBP system. Instead of wrestling with some existing language’s limitations, I invented a PML—Portable Meta Language—on the fly. No committee. No formal specification. No PhD thesis justifying its existence.

The PML expressed only what I needed: the bare semantics of my kernel design, nothing more. Then I wrote a transmogrifier in a couple of afternoons. Maybe it was hours. I honestly don’t remember, because it felt easy.

That transmogrifier produced working code in three languages—Python, JavaScript, Common Lisp. This generates some 900 lines of Python. Non-trivial according to line counts, trivial according to cognitive load.

Later I repeated the experiment with a Forth-like language. I stole my earlier PML, modified it to suit Forth’s semantics, wrote a new transmogrifier. A few hours of work total. Changed the PML syntax along the way because I felt like it. Took a few extra minutes.

No head-scratching. No premature formalization. No months debugging type systems or fighting the host language’s opinions about how code should be structured.

Scheme to JavaScript: A Case Study

Want proof that this works on real code? Take Nils Holm’s prolog6.scm—a working, debugged partial implementation of Prolog in Scheme. The most significant aspects of Prolog laid bare: exhaustive search, backtracking, and cut.

Because it’s working code, I didn’t need to type check it further. It doesn’t need semantic analysis. It just needs syntax mapping. Scheme’s semantics to JavaScript’s semantics. A purely mechanical transformation.

I documented the conversion using only OhmJS. The diary runs through every step—pattern matching the Scheme forms, emitting equivalent JavaScript, handling edge cases. The result? Working JavaScript that does exactly what the Scheme version did, because we never touched the semantics.

This is what syntax-as-a-skin-over-semantics looks like in practice.

The Path Forward

There’s no longer any reason to unify all useful paradigms into a single language. We don’t need to keep trying. The tools exist now to move between paradigms as fluidly as we move between file formats.

Write your logic programming in something that looks like Prolog. Write your concurrent code in something that looks like asynchronous message passing. Write your data pipelines in something that looks like electronics schematics. Then use Common Lisp or Scheme or some other high-level assembly language like JavaScript or Python as your LCD for the actual execution semantics.

Text-to-text transpilers, driven by PEG grammars (like OhmJS) and rewrite rules, transform between the surface syntax humans prefer and the semantic core the machine executes. Peepholing tunes the emitted code, and eventually might be turned on itself.

When such systems emerge—and they will, because the tools are already here—we’ll look back at our attempts to unify paradigms in single languages the way we now look at assembly programmers who refused to trust compilers. Noble. Understandable given their constraints. Completely unnecessary given ours.

The goal isn’t to make syntax unnecessary. The goal is to make syntax cheap—cheap enough that we can afford to use the right syntax for each problem, rather than forcing every problem through the same syntactic sieve.

Paradigms are important. Syntax? That’s just a rendering choice.

References

Cordy, James R. An Orthogonal Model for Code Generation. PhD thesis, University of Toronto, 1986. https://books.google.ca/books/about/An_Orthogonal_Model_for_Code_Generation.html?id=X0OaMQEACAAJ

Davidson, J. W., and C. W. Fraser. “The Design and Application of a Retargetable Peephole Optimizer.” ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems 2, no. 2 (April 1980): 191–202. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/220404697_The_Design_and_Application_of_a_Retargetable_Peephole_Optimizer

Holm, Nils M. Prolog Control in Six Slides. 2019. https://www.t3x.org/prolog6/

Holt, Richard C., James R. Cordy, and David B. Wortman. “An Introduction to S/SL: Syntax/Semantic Language.” ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems 4, no. 2 (April 1982): 149–178. https://doi.org/10.1145/357162.357164

Holt, R. C. “Data Descriptors: A Compile-Time Model of Data and Addressing.” ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems 9, no. 3 (July 1987): 367–389. https://doi.org/10.1145/24039.24051

OhmJS: A parsing toolkit. https://ohmjs.org

Forthish portable meta language implementation. https://github.com/guitarvydas/forthish/tree/main/frish

PBP (Parts-Based Programming) Development Repository. https://github.com/guitarvydas/pbp-dev

RWR Specification. A DSL for Rewriting Text. https://github.com/guitarvydas/pbp-dev/blob/main/t2t/doc/rwr/RWR%20Spec.pdf

Ohm in Small Steps. Scheme to JavaScript. https://computingsimplicity.neocities.org/blogs/OhmInSmallSteps.pdf

t2t: Text-to-Text Transpiler. Code repository. https://github.com/guitarvydas/pbp-dev/tree/main/t2t

Experiments with text-to-text transpilation. https://programmingsimplicity.substack.com/p/experiments-with-text-to-text-transpilation?r=1egdky

Text based portability. https://programmingsimplicity.substack.com/p/text-based-portability?r=1egdky

See Also

Email: ptcomputingsimplicity@gmail.com

Substack: paultarvydas.substack.com

Videos: https://www.youtube.com/@programmingsimplicity2980

Discord: https://discord.gg/65YZUh6Jpq

Leanpub: [WIP] https://leanpub.com/u/paul-tarvydas

Twitter: @paul_tarvydas

Bluesky: @paultarvydas.bsky.social

Mastodon: @paultarvydas

(earlier) Blog: guitarvydas.github.io

References: https://guitarvydas.github.io/2024/01/06/References.html

Would PML be an IR?

I have some perplexity about the "1970s trap" paragraph. Let me start by saying that I am an amateur programmer, so I could be wrong.

Before the C was invented, there were many programming languages in use (Fortran, Algol, PL/I, Lisp...). The C language was invented in 1973 only for writing the operating systems (Unix in that year). After 1973, these events happened:

_ programmers started to use C for writing programs outside from operating systems.

_ many new languages were invented, imitating the syntax and the behavour of the C language (C++, Objective C ...).

_ many older languages were partially or totally dropped.

I suppose this trend happened for a simple reason: linking more executables written in different programming languages, in those years, was complicated. Using C as multi-purpose language seemed a viable solution for solving this problem.

I remember an interview to Frances F. Allen:

https://www.noulakaz.net/2020/05

Here an excerpt of the interview:

Seibel: Do you think C is a reasonable language if they had restricted its use to operating-system kernels?

Allen: Oh, yeah. That would have been fine. And, in fact, you need to have something like that, something where experts can really fine-tune without big bottlenecks because those are key problems to solve. By 1960, we had a long list of amazing languages: Lisp, APL, Fortran, COBOL, Algol 60. These are higher-level than C. We have seriously regressed, since C developed. C has destroyed our ability to advance the state of the art in automatic optimization, automatic parallelization, automatic mapping of a high-level language to the machine. This is one of the reasons compilers are… basically not taught much anymore in the colleges and universities.